Trudge On, Soul is available on Amazon. This preview includes the Prologue, Chapter 1, and Chapter 2. (Click to jump to that section.)

Trudge On, Soul is available on Amazon. This preview includes the Prologue, Chapter 1, and Chapter 2. (Click to jump to that section.)

Click here for the original blog, pictures, and videos (recommended after reading the book to avoid spoilers).

Prologue

My piano teacher grunted, tapped a page of Teaching Kids Piano. “Here, Warren. Your eyes stay here.”

Outside, an engine sounded like a chainsaw. I concentrated on the piano keys: plunk, plunk, plunk.

BRAAAP! The engine revved and my heart raced. I didn’t want to play piano.

Plunk, plunk, plunk.

Her son zoomed past the window, and my eyes stole a glance. But I missed him—and several piano keys. He jumped and spun donuts on a motorcycle while I plunked the piano. How was that fair? Maybe I needed to grow up first. Second-graders played piano—sixth-graders rode motorcycles. I was four grades away.

She snapped the book shut. “Go home and practice, practice, practice. You are talented, don’t you go and waste that.” She ushered me to the door. “Straight home and practice for twenty minutes. Okay?”

She expected me to nod, so I did. The door shut, and I started for home to practice so one day I could play ragtime music like my mom. But with every step, the passion drizzled—perhaps through the holes in my pockets. Halfway down the long sidewalk, my pockets were empty. I stopped. The high-pitched wail of the engine on the other side of the house beckoned like a siren’s song. I turned around. Nobody would care if I got a better look, would they? I circled the house where, finally, I could watch without constant interruptions like: Remember your fingering. Don’t forget B-flat.

From behind a tree, I saw tires spinning, dirt flying. Merely watching made me feel older. Like a third-grader—three more grades to go before I could ride.

The bike faced me and the engine screamed. Run? Too late. He skidded to a stop three feet away and stared at me. With nothing to lose, I stepped forward.

“Why do you get to ride motorcycles, and I have to take piano lessons?” I yelled over his rattling engine.

He killed the bike. “You’re Warren? The piano kid?”

“War,” I corrected. Warren the piano kid was not what I wanted the sixth-graders calling me.

“Okay, War. And you want to ride my dirt bike…”

His eyes sparkled with laughter, not the fun kind, so I cut him off. “My mom wants me to take motorcycle lessons. She’ll pay you, of course. Like she pays for my piano lessons.”

Dollar signs replaced the laughter in his eyes. “Alright, I’ll give you lessons.”

I hadn’t expected that to work. I couldn’t pay him. Unless I told Mom piano lessons went up, and I needed to bring cash, instead of a check every week. Yeah, brilliant!

He kicked life into the bike, and my grin wrapped around my face. Kickstarting a motorcycle was the manliest thing in the world. With a single thrust, lifeless steel became a growling tiger, ready to run fast and hard. Seeing him resurrect the beast bumped me to fourth grade and sixth felt closer than ever.

He dismounted. “Climb on, hold this lever. Step there to put it in first. Then twist the throttle a bit and slowly release the lever. Easy as pie.”

I swung my leg over the seat, gripped the handlebars, and pointed my toes to reach the ground. Fifth grade! Heart pounding, I did what he said. Well, almost. I popped the clutch, the bike lurched, and I fell on my butt.

He picked up his motorcycle. “Too much gas, little guy. Try again.”

A half hour later, I rode circles through his yard smiling bigger than Christmas. Boom, sixth grade!

I walked home dreading the long wait until my next lesson but, turned out, I didn’t have to wait. My brilliant plan crashed that night—Mom knew. How did Mom always know? In a heartbeat, I was booted all the way back to second grade.

Four years later, to save on 1970s gas prices, my dad bought a Suzuki 250—the coolest machine ever. Not a true dirt bike, but it handled the dirt roads around our house every bit as good. The throaty engine announced his arrival home each day, and I’d run outside for a ride before he parked in the garage. One winter, he put chains on his tires and towed us through the snow on sleds. I loved riding with my dad but longed to drive myself—like my one time after piano lessons.

Sixth grade arrived, but instead of riding motorcycles in the fields around our house, I often hid out there to escape bullies. That’s when I met Harvey—my mentor through adolescence. Harvey was a timid man who only existed in my head. He introduced himself to me in sixth grade while I walked home nursing a fat lip (through the fields).

I can protect you from them, he whispered in my mind.

I took one look at him and laughed. As if. He wore gold-rimmed glasses and spoke in a scratchy, whiny voice. He looked like the kind of guy who made fusion reactors, not one who fought bullies.

Give me a chance. I’ll prove it, he said.

Thanks, but I don’t think so.

Later, while looking at my swollen lip, I reconsidered. If Harvey could prevent this from happening again… Okay. Keep me safe, and I’ll do what you say. I’m tired of looking stupid.

Harvey moved in. I imagined him in a small room with a bed, a bathroom, a desk, and eventually a computer. Four tiny, round windows let him see the world through my eyes and the holes in my ears.

Harvey tapped his fingers, looked at me over his glasses, and established the guidelines. You must never question me. Do what I say, when I say. Agreed?

I nodded. What did I have to lose? If it didn’t work, I’d boot him out.

No talking to girls. No rock climbing, motorbikes, or photography. Too dangerous and expensive. Avoid risk. He pointed at me. Keep your mouth shut, ideas to yourself, and avoid attention.

I scowled. No motorcycles?

His head shook.

I agreed—for now.

Turned out, life was a peaceful river when I followed Harvey’s advice. A creative genius, he used imagery, stories, and poetry to keep me in line. A stranger walking down my side of the road became an escaped psycho from an asylum, so I crossed the street. A flat bicycle tire after school? A nail-biting thriller as I rushed to patch it and ride away before hooded villains emerged. Everything scared Harvey, so almost everything scared me. Some mornings, his finger hovered thirty seconds above his light switch because of his fear of static electricity.

When I ignored Harvey, I often ended up feeling like an idiot. Like in ninth grade when I wanted to give my crush a Christmas present.

Don’t do it.

Why?

Girls are a risk…

But I remembered her smile and forgot his words. I wrapped the package, stuffed it in a brown paper sack, and decided to give it to her the next day. Harvey pretended to wash his hands then held them up.

Forget Harvey. She’d love the present and me.

The next day at school, I avoided her—even when sitting next to her in advanced typing class with the bag under my chair. My normal, calculated, lunch routine usually crossed her path, but not that day. After the final bell, she stood in line as yellow school buses approached for the last trip home before the two-week, winter break.

I played the scene in my head. Suave, I’d hand over the gift as her eyes lit and a shy smile appeared. “Call me,” she’d mouth. By the new year, I’d have the cutest, smartest girlfriend in the school.

Success hinged on suave, and suave never showed. Her bus belched to a stop, the doors opened, and she stepped aboard. A large, yellow thief was stealing my dreams.

Whew. Harvey fell onto his bed. Close one.

Then I yelled her name and ran down the sidewalk while Harvey screamed in horror. She stopped, two steps high, and looked down at me. I handed her the sack, my eyes wide and hands shaking.

“Merry Christmas,” I said.

She took it, thanked me, and the bus swallowed her. I walked away a superhero, proud and confident. But rather than calling her during the break, I listened to Harvey rant—for two weeks solid.

You fool, she’d never go for you, he said until I believed him.

A fallen hero, I went back to school a supernerd. She said “Hi”; I said “Hi”, then I walked the other way. I never really talked to her again.

You feel pretty stupid, don’t you? Harvey nodded, answering for me. Next time, are you going to listen to me?

Without a doubt.

After the Christmas nightmare, I stuck to most of Harvey’s instructions without debate. Except when it came to motorcycles. I turned sixteen, got my driver’s license with a motorcycle endorsement, and hoped that once in a while my dad would let me ride his new Nighthawk to school. Nope. He sold it and bought a small car I could drive. Because motorcycles were too dangerous.

With Harvey in control, daydreams became routine. They kept me out of trouble, so he used exciting thoughts to distract me. My eyes glazed, and I escaped into fantastic worlds. A space pirate. A knight. A National Geographic photographer riding a motorcycle through Africa while fighting ninjas. And I always got the girl.

I thought Harvey would be gone by the time I turned twenty-one. Nope. I hadn’t realized the temporary position I filled to get me through my teenage years would haunt me the rest of my life. The confused little boy dreaming of motorcycles became a confused adult dreaming of motorcycles. I grew taller, married young, and before I knew it, we were a family of five. I was an overgrown kid trying to be a father, husband, and employee.

Harvey stalled the purchase of my first motorcycle until my mid-twenties. Then he made sure I avoided rainy skies and handled the throttle like it was made of glass. I paid mechanics to change my oil and putted around back roads. My riding experience was a notch above plastic motorbikes at theme parks rotating to circus music. Exactly what Harvey wanted.

True to his word, Harvey had kept me safe. He’d also pushed me to get good grades and think about my future. Instead of photography, writing, or psychology, I spent thousands of dollars and years in school earning the most boring (yet reliable) degree in the world—accounting. A conservative route because I was afraid to fail, afraid to succeed, and afraid to try.

When I first saw an adventure motorcycle, an SUV on two wheels, my mind raced to the exotic places I’d never go on it. The machine—the love-child of an African safari four-wheel-drive and a sleek Italian sport bike—deserved to be in a centerfold. I put one hand on the shoulder of my five-year-old son Curtis and said, “Someday, I’m going to Alaska on one of those.”

My bold claim had barely left my mouth before falling splat. Another hollow dream, another gooey mess on the floor—the sad life of a depressed daydreamer.

The daydreams helped me escape my boring life. For instance, while inching through traffic—a sea of blinking brake lights—I’d imagine myself pulling victims from a burning car. Or exploring Africa. Anything to make me forget that I was spending most my life sitting in cubicles and cars doing nothing. Daydreams kept me sedated and stuck. Used right, dreams pushed athletes to excel and scientists to cure diseases. Mine were like ecstasy and opium—they thrilled, soothed, and left me dazed.

I’d dreamed of a new life for years, and one eventually found me. My religious beliefs evolved, and I walked away from the foundation of my life—the Mormon Church. A computer business I’d started and been running for several years failed, and I went bankrupt (as predicted by Harvey). The final blow, several years later, leveled me: my wife filed for divorce. When I finally stumbled to my feet, covered in dirt and grime, my life was in ruins. I turned on Harvey, eyes burning red.

I trusted you. I did everything you said and it destroyed me! I’m thirty-five and a complete failure.

He glared back. Oh, nice. Blame me for this. That is so like you. This mess is the result of your lazy, narcissistic…

We tore at each other, vicious and unrestrained. Thirty years of anger, frustration, and pain erupted in a dirty brawl between the life I was supposed to live and the one I’d wanted. I’d followed his rules, but where was the life he’d promised? I fought like a desperate man against tyranny.

Once we lay bloody, too exhausted to lift another accusatory finger, the truth settled. We were stuck with each other, and it was time to rebuild.

I quit my job—a demanding, promising job at a large software company in Redmond. I quit against Harvey’s advice. I quit against everyone’s advice—even my manager’s.

“Warren, I don’t see passion in you anymore. What happened?” My boss drummed fingers on his desk.

“It’s gone. And I don’t know if it’s ever coming back.”

He tried to help, but I wouldn’t be saved and gave six weeks’ notice. My life was upside down. Three kids to support, and I quit without a plan. What was I doing?

Your life is in shambles, sure, Harvey said. But good hell, why shoot yourself in the foot?

Because the kids are spending too many hours alone in my two-bedroom apartment.

Their mother was busy reliving her twenties—stolen by marriage at eighteen and a child at nineteen. Aubree was in middle school, Curtis in his last year of elementary, and Mikayla a little third-grader. So I quit my job. My extensive work-related travel and three-hour daily commute was leaving them to parent themselves.

You have nothing to lose now. You threw away your career, Harvey said.

I have my kids, I snapped. The one thing in this world I can’t ever lose.

Right, your kids. Another reason bailing on your job was boneheaded.

Harvey was wrong. In my downtime, I wrote the fantasy novel I’d been talking about for ten years. Within a couple months, I took a position that let me be more of a father to my kids—low-stress and forty-hours-a-week. The downside was less pay and stuck in a cubicle, but the short twenty-minute commute and four weeks’ annual vacation made up for it. The kids and I played video games, took road trips, watched movies, and played Dungeons and Dragons. Two years later, I married Sandi, the sweetest woman ever. She loved me, my kids, and they loved her. We bought a house. My life was no longer rubble.

Congratulations, Harvey said. You’ve turned your life around. See what happens when you listen to me?

He was right. Why, then, did I still feel lousy? I often dreaded falling asleep at night because morning and work were a blink away. Sometimes I set my alarm to go off every two hours to make the night longer. My life was good. Why wasn’t I?

Curtis struggled in middle school. His grades dropped, and he was called into the principal’s office several times for fighting. Unlike me at his age, he hit back when somebody took a shot at him. I was proud of him for standing his ground, yet concerned. After a rather intense session with my therapist, I made a decision.

I’m going to South Africa with Curtis, I told Harvey. Not because I want to but because he needs it. Then I’m taking solo trips with the girls and Sandi anywhere they want to go in the world.

Whatever. He was too used to my daydreams.

Officially, the trips were for the kids—which was why I followed through. Curtis in Africa, Aubree in Italy, Mikayla in Greece, then Sandi in Costa Rica. One per year for four years. They changed me. The Spirit of Adventure seemed to be healing the scared little boy inside my forty-year-old shell.

I felt better than I had in over twenty years, but too many nights I tossed, watched my alarm clock, and dreaded 6:00 a.m. What was I missing? The little boy in me daydreamed, again, about an Alaskan motorcycle trip.

Chapter 1

“Dad, I’m buying a motorcycle,” Aubree said over the phone.

A motorcycle? Aubree? Who was this stranger sounding like my daughter? A college mate in her dorm must have pinched her cell.

“My bicycle has a flat, and I’m tired of riding buses,” she said.

“You know … tires can be patched.”

“You can’t talk me out of it. I’m buying one.”

Absolutely not! Harvey jumped to his feet. Not in Seattle rain and traffic. She’ll be killed.

“Hmm,” I said to her. My standard response to buy time while arguing with Harvey.

Harvey’s eyes narrowed. Hmmm is the wrong answer. Try, “Hell no, you aren’t.”

Legally an adult and bullheaded like me, if Aubree said she was buying a motorcycle, she was buying a motorcycle. What right did I have to say no? Hypocrite dad gets one, but his kids have to ride bicycles? Each of my kids had spent hours behind me riding through the countryside—we had fond memories of riding. Of course she wanted a motorcycle.

Why are you hesitating? This is a no-brainer. Tell her no!

Think, Harvey. If I say no, she’ll get pissed. Every time she rides, she’ll feel a rebellious ‘stick it in your face, Dad’ attitude. You want her riding angry? If I stay neutral and talk her through it, she’ll probably back down. You know how she gets these hair-brained ideas.

Yeah, exactly like her dad. But what if she doesn’t back down?

Then I’ll help her find a reliable, good deal and we’ll ride together … where I can teach her how to be safe.

He kicked the wall—which he did when he was pissed that I was right, and was probably the source of most of my headaches.

I shut my eyes and massaged my temples. “A motorcycle, eh? Interesting. What are you thinkin’?”

She emailed me links to several bikes on Craigslist. We rejected some, called on others. A red Honda Rebel 250—small, light, and covered in chrome—won her heart. The next weekend she came home and bought it. We rolled the shiny new machine into the street for her first ride. Our helmets had intercoms, so I could talk to her from the driveway as she practiced riding up and down the road.

I started her bike. “Climb on, hold this lever. Step there to put it in first. Then twist the throttle a bit and slowly release the lever. Easy as pie.”

Copycat. Better warn her about popping the clutch, Harvey said.

As she settled on the seat and gripped the handlebars, I said, “Make sure you go soft on the clutch and gas until you get a feel for them. Or you’ll end up on your butt.” I paused—Aubree wasn’t the type that worried about falling on her butt. “And scratch your chrome.” That got her attention. She clicked into first gear; the bike jerked forward. Careened left, sputtered, reeled, swerved right, sped up. She rode a giant ‘S’, weaving up the road like she was riding a drunk bull about to throw her. I put my hands on my helmet, winced, and bit my tongue because I didn’t want to scare her by screaming into the intercom.

Harvey did scream. She’s going to hit that car! Or kill someone … how could you let her—

Suddenly, her motorcycle straightened, centered on the road, and putted a hundred yards ahead. She’d found the knack. I jumped and pumped my fists—without making a sound because I didn’t want to break her concentration.

“Dad! What do I do? How do I stop? I don’t know how to turn!”

I forced a calm voice. “You’re doing great, Aubs. Pull the clutch, ease the throttle, and roll to a stop.”

She did, turned around, and rode back. With each pass up and down the road, she added new skills—braking, turning, stopping. Later that day, I followed her on my Honda Magna through the neighborhood and continued the instruction. “Watch that car up there, they might not see you. Cover your clutch and be ready to brake.”

For the next couple weekends, she came home from college to ride. We rode around lakes, through forests, and up mountains while chatting nonstop about motorcycles, boys, and school.

One evening after riding, Aubree pointed at my monitor. “What’s that, Dad?”

The centerfold adventure bike had returned to my computer desktop.

“A new bike I’ve been reading about. A Triumph Tiger 800XC.”

“Sexy.”

“Sexy as hell. I’m going to see it tomorrow.”

“No!” Her eyes popped wide. “Are you buying it?”

“Nope. Just looking.”

Damn straight you’re just looking, Harvey said.

The next day, Sandi and I went to the Triumph dealership. In the middle of the showroom floor, a white Tiger 800XC made my jaw drop. A perfect blend of sleek and tough. Fast and nimble on pavement, yet capable on mountain trails. I gawked like a teenage boy at the beach. More than two wheels and an engine, this was the new BMX bicycle I never had as a little boy, the motorcycle I never had as a teenager, and the adventure bike I’d dreamed about for fifteen years as an adult.

Walk away. Now.

Don’t worry, I’d find a used bike if I got one. I’m only looking.

Fine. Look but don’t touch. Like at the beach.

Sandi nudged me. “Go sit on it!”

What’s she doing? Harvey threw up his hands. She should be jealous of hot motorcycles. Whatever, sit on it. But you look like a frickin’ idiot, close your mouth. If you are going to sit on it, at least act like a man.

I cleared my throat, nodded, and frowned like a man. “Okay, I’ll sit on it.”

The seat was higher than my waist, and I caught my foot trying to swing my leg over. My face reddened; Harvey laughed.

Nestled in the saddle, I pointed my toes to reach the ground like I had over thirty years ago. This bike is too big, tall, and powerful. No way I can ride it.

Glad we’re on the same page, Harvey said.

“How about a test drive?” A hand appeared from nowhere. “I’m Jason.”

“Sure.” Sure?

Sure? What in the hell are you doing? Harvey said.

Ten minutes later in the parking lot, the Tiger growled beneath me. What the hell was I doing? My Honda Magna sat low to the ground—a cruiser—where I leaned back on a recliner with wheels. This was a monster truck. I couldn’t drive monster trucks. What if I crashed? I thought of Aubree, nervous and determined on her first ride. She’d managed; I could too. I twisted the throttle, released the clutch, and rode into the street. The fear vanished. As my instructor had said after piano lessons many years ago, it was “easy as pie.”

The bike cornered like a tiger dodging trees in the jungle. I slowed at a light—the fear returned and I tried to remember how to ride. Pull the clutch. My boot tapped air. Where’s the rear brake? There it is, whew. I pointed my toes to the pavement for balance and stopped.

A truck stopped to my right.

I think he’s looking at you, Harvey said. Keep your eyes on the stoplight.

Harvey hated eye contact. Eye contact signs the eye contract, he’d said. Then you have to talk to them. They might not like you, you might say something stupid, or they may try to sell you something…

Light’s about to change. Harvey looked at the truck. Shit, he’s rolling down his window.

“Hey!” a voice yelled.

I flipped my visor and met the man’s eye. Contract signed.

“What is that?” He pointed at the Tiger, nodding approval.

“A motorcycle!” Pride and enthusiasm filled my voice but crumbled to ash when I heard my words.

Harvey winced. See what I mean? Never sign that contract.

“An Adventure Tiger. I mean a Triumph Alaska XL.” No, all wrong. Somewhere I’d missed an 800…

Stop. Harvey held his head. Just stop, don’t even try to fix it. You are creating a dangerous rift in your motorcycle karma.

Truck guy’s mouth turned up slightly. A comforting expression that said, don’t worry son, it’ll be okay. The same look a father gives his toddler who’d accidently pooped his pants. Hang in there little buddy, you’ll get the hang of it…

The light changed, and I let the truck move ahead. I needed to escape so turned onto the freeway and gave the throttle a healthy twist. The Tiger sprinted like a cheetah and I fled from the fiasco back at the intersection.

Oh, this is nice, Harvey. Wait. Is that a smile on your face?

No! He scurried from the window. I was watching traffic.

Three cruisers in my life, and there’d never be another—the end of my recliner era. Back at the dealership, I weaved through the parking lot standing on the pegs (something you can’t do on cruisers or sport bikes). Rather than blacktop, I saw Alaska and bears. I returned the bike to Jason and pulled off my helmet. Sandi must have noticed my eyes burning.

“You should buy it. You’ve been saving for years, you have the cash. Do it.”

I did.

That evening, I pulled into the garage, soaked from rain, and parked for the night. But when I walked into the house, Aubree grabbed her helmet. “Let’s go, Dad. Gimme a ride!”

“But the rain!”

“So?” She headed for the door. We rode.

Over the next few weeks I showed off my adventure bike with a smug grin. “I’m going to Alaska on that, in two years.”

The two-year timeframe let me boast, but not take the trip seriously. Alaska talk produced envious smiles and fueled an addictive ego buzz that kept me bragging about an adventure I never expected to take.

Sandi liked riding with me on the tiger, but seeing Aubree’s enthusiasm inspired her to take a class and get her own motorcycle endorsement. The Magna became Sandi’s bike. We’d fire up the three bikes, Mikayla would climb on behind me, and we’d all ride off together. All but Curtis. At sixteen, riding “bitch”—as hard core riders said—was below his cool threshold.

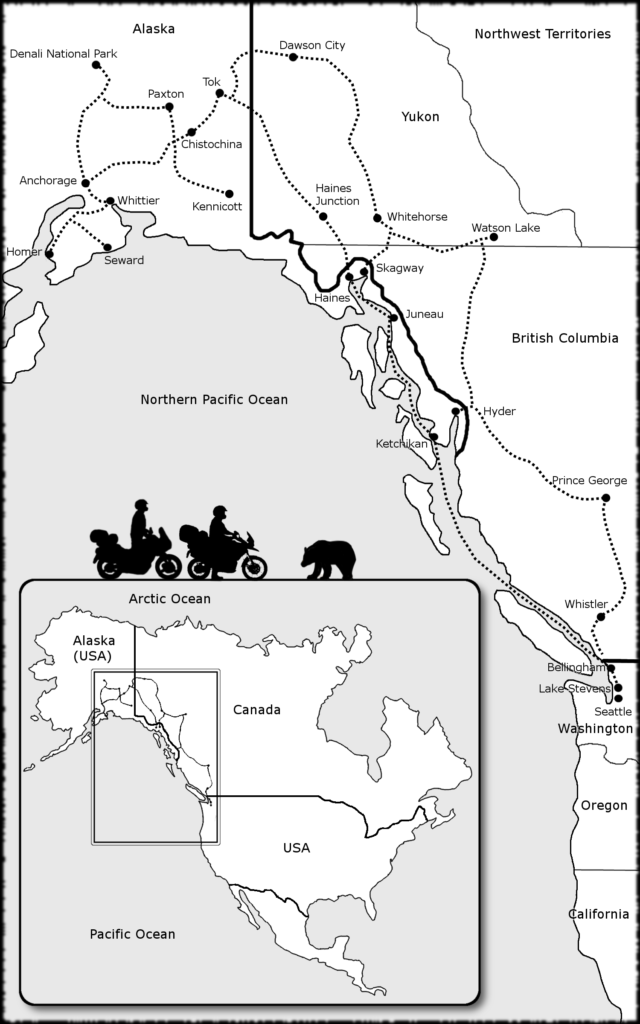

In the fall, my good buddy, Mike, called. “War, I need us to go to Alaska on motorcycles.” A heart attack had recently taken his father and the ride remained unchecked on his dad’s bucket list. Mike wanted to take his ashes.

You can’t agree to that, since we aren’t really going, Harvey said.

He doesn’t even ride. Don’t worry. The meaning Mike brought to my fake trip was touching.

“I’m thinking next summer,” Mike said.

Tell him no, Harvey said. He’s serious about this.

“Alaska is brutal, even for an experienced rider. I don’t think one year of riding could prepare you enough. I’m already planning on going in two years, that’d be a great time frame for you to get a bike and log some experience.”

“That makes sense. Okay, two years.”

Harvey grunted. Whatever. He’s gonna be pissed when you bail.

Relax, he doesn’t even have a motorcycle.

Two weeks later, he had a motorcycle. A Suzuki, eighty miles away, won his heart. Despite no face-to-face meeting, he decided she was the one and arranged an introduction. We took my Tiger to pick her up. Two men on one bike, and we avoided the “B” word. A ‘don’t ask, don’t ever tell’ situation—except Sandi took an incriminating picture as we left.

Our egos took a hit, but for a worthy cause. We parked on the curb next to his shiny orange vixen waiting in the driveway. Mike wasted no time: smitten like he’d won a date with the prom queen, he stepped up and gave her a firm smack on the seat. He bought her, named her Gertrude, and they were built for each other—short, stocky, and hewn. She complimented his Scottish looks as if she’d just gotten off a boat from Edinburgh.

“Your Triumph needs a name,” he said.

“Hmm…” Kate? Amelia? Latifah? None felt right. “Tiger,” I said.

“That’s the model. Pick a woman’s name.”

“Tigress?”

“Tiger, then. And here I thought you were the creative one.”

*

I don’t like this, Harvey said. These events with Aubree, Sandi, and Mike. They don’t seem random.

Was the Spirit of Adventure leading me to Alaska?

Curtis turned a deeper green each time Aubree, Sandi, and I rode. Aubree let him ride her Rebel on our street, and he got worse. Loaners do not satisfy the motorcycle hunger, and I had passed a genetic craving to my son. I worried he’d never shake the lime tint if I didn’t do something.

One cold October day, we left early to watch the Sounders play soccer in Seattle.

“The game isn’t for three hours. Why are we leaving now?” Aubree asked.

“It’s a surprise. Punch in that address.” I handed her a torn paper.

“What? Where we goin’?”

“To get something for the family.”

“Dad found something on Craigslist!” Aubree sang, pointing her fingers in a funky dance.

They buzzed with excitement and speculation for the entire forty-five-minute drive.

Aubree glanced at her phone. “Turn right, and it’s on the next street.”

I passed the house.

“No way!” Curtis covered his mouth.

“What? Where?” The girls searched, but the prize hid on the other side of the house.

“Are you serious, Dad? This better not be a joke,” he said.

I flipped around and pulled into the driveway. At the end stood a shiny red Ninja.

I still can’t believe you are buying a crotch rocket, Harvey said.

Mikayla punched the back of my seat. “No fair! I can’t drive it yet.”

With the fall rain, motorcycle prices plummeted. This bike, with a few scratches, dings, and needed repairs, was a great deal. I gave Aubree the keys to the car and followed them to the game on the Ninja.

“One rule,” I said, later, as we admired our new sport bike in the garage. “Nobody rides unless I’m with them.”

The Ninja Rule, one of my best inventions, belonged in the Family Rules Hall of Fame. I wanted to spend more time with my son, he loved motorcycles, and I had a Ninja. Simple math. He took the class, got his endorsement, and we rode all winter. After work, on the weekends, and in the fog. If Dr. Seuss had ridden motorcycles with his son, he’d have put it this way:

We rode our motorcycles in the dark,

we rode our motorcycles to the park.

We rode them through the icy cold,

we rode them down a slippery road.

We liked to ride our bikes, you see.

So we rode them, constantly.

Books littered the coffee table for months as we read about technique and safety. Then we practiced, quizzing each other as we logged thousands of miles. Curtis later bought the Ninja from me and rode it everywhere—his sole form of transportation.

Harvey wrinkled his forehead. You aren’t really thinking about that stupid trip north, are you? Cause it sure seems you’re headed in that direction.

I rolled my eyes. Of course not!

But puzzle pieces were falling into place and the forming picture had mountains, glaciers, and bears. With a year to go, Mike and I started throwing out an occasional “we should talk Alaska.” Or, “I want this trip to change me.” I figured three weeks on a motorcycle trip to Alaska had to do something good for me. Right? Of course it would.

We’d planned on off-roading in Alaska and needed practice. Our bikes needed to play in the dirt, so we scheduled a day to ride some trails and went to a local ORV (off-road vehicle) area. But we couldn’t find a way in. The first entrance to the trails had two hills, both too steep. Further down the road, we found an easier way in and hit our first off-road—whooping and hollering like prospectors who’d struck gold in the Klondike. I bounced over a log—stick—and yelled, “Adventure!” Three minutes later, dejected and humiliated, we walked our bikes back down the path. Our adventure spirit had been killed by a dip in the trail that we didn’t dare cross. Mike apologized to Gertrude, telling her it was his fault. I couldn’t look Tiger in the headlights.

See? You’d never survive Alaska, Harvey said.

I nodded, and he gloated.

I need an old dirt bike to practice on.

Harvey’s eyes teared and his mouth quivered. Dirt bike? Who are you? I don’t even know you anymore. He muffled a sob, ran into his bathroom, and slammed the door.

Jason, the guy who sold me Tiger, and I had become friends. He helped Curtis and I find a couple used dirt bikes—winter fixer-uppers. The three of us spent two months in the garage pounding on them. Books and YouTube videos showed us how to crank ratchets and, after many bloodied knuckles, we got them running. In early March, Curtis and I took them to the ORV area. When I looked at the two dirt bikes strapped to our old, rickety trailer, my stomach gurgled.

Shit. Now we have to ride them.

No, you don’t. Get back in the truck and go home.

Curtis started unhooking straps. I pulled boots and protective gear from the back of the truck.

“You have any questions, bud? You worried at all?” I asked in my confident voice.

“A little, but you’ll show me what to do.”

Harvey howled. Know what? I don’t even care anymore. I want to see you ride that thing. This will be hilarious.

We unloaded the bikes. Curtis sat on the CRF150, decked out in gear, while my boots and chest protector sat on the tailgate. I took my time, checking ‘important’ stuff on the bikes. Eyeing bolts, kicking tires…

“So remember, bud, choke it before you start but don’t forget to turn the choke back off after a few minutes.”

He knew, but smiled and nodded.

When I finally kicked alive my CRF250R, it rumbled and pulsed like a bull waiting for the pen to open. The same two hills Mike and I shied from months ago taunted me, large on the left and small on the right. I rested my boot on the foot peg and my leg shook—and not because of the vibrating motorcycle.

I changed my mind. I don’t care how funny it would be. Don’t do this! Harvey said.

Our bikes thundered.

I turned on my intercom. “All set?” Even though I knew he’d been “all set” for ten minutes.

“Yup! Let’s do it.”

Harvey opened his mouth to speak, but I flicked the throttle to shut him out. A leopard roared and shot forward with a ferocity that nearly threw me. Fingers locked, the bike dragged me until I gained composure. I steered left. Why had I chosen the big hill? Maybe that’s what Harvey had wanted to say: take the small hill.

I shifted up and hit the base with my heart racing faster than the engine. The back tire spun, I leaned forward, and climbed. Right up that hill. Almost.

Near the top, my ferocious leopard sputtered and died. I imagined rolling backward, fishtailing, and tumbling head-over-motorbike to the bottom in a heap of dust, pain, and twisted metal. I vaulted off the bike before that could happen, dug my boots into the sand, and pushed. Nothing. The bike slid back; I pulled the front brake.

“Need help, bud,” I said. Thank heavens for the intercoms.

Curtis zipped over the smaller hill, parked, ran up the back of mine, and pulled on my front tire—rolling until the bike cleared the top. Then I coasted down the other side hyped on adrenaline. I’d won! Scared the bejeezus out of me and, technically, I didn’t completely succeed—but I checked the ‘win’ box anyways. Trails cut through pines, and we explored the forest while showering ourselves in mud—giddy like bear cubs in a salmon farm.

“Thanks for getting these, Dad. That was awesome,” Curtis said as we loaded the trailer.

Exhausted, we returned home caked in muck. The next week we took the girls out and the fun continued—we all loved dirt biking. We added a third, fixed it up, and rode most weekends.

That spring, I rebuilt an engine, replaced a piston and cylinder, installed valves, and serviced and maintained three dirt bikes top to bottom. Off-road, I rode long days in the mud, sand, rocks, and gravel. I crashed, jumped, and climbed hills. On the pavement, Curtis and I traversed the highways and byways of Seattle in all types of weather. The Spirit of Adventure had used friends and family to prepare me.

Harvey, I said, four months before the scheduled departure. You need to know something. I’m going to Alaska.

Chapter 2

Two months before our departure date, Mike and I were caribou in the headlights of an oil truck barreling down the Dalton Highway. Alaska loomed, and our entire plan consisted of five simple words:

1. Go to Alaska on Motorcycles

2. …?

You and your big mouth, Harvey said. Telling people you’re riding to Alaska. You’re gonna feel like a putz when you cancel.

Harvey was right about my big mouth, but not about canceling. My ego was too vested and I wouldn’t bail on Mike—even though dread nipped at my heels like an Alaskan wolverine. We needed a better plan.

In June, Mike came out to hash ideas. We flipped through maps, books, and notes, but I didn’t know where to start.

I turned another page of the guidebook, but my mind wandered. “We could ride dirt bikes and do this tonight.”

Mike snapped his book shut. “Works for me.”

An hour later, roaring down an ORV trail, I underestimated a hill and found myself floating through space and time. My arms flailed. Clouds? Why was I looking at clouds? Then my motorcycle blocked the sky, flipping in the air above. Then—ugh—my back thumped the ground.

Aahhh! Harvey screamed as a shadow grew around me.

I kicked like an upside-down beetle, and the bike slammed to the ground, pinning my feet. At least the beetle dance had spared my legs and chest.

What happened? Harvey felt around for his glasses. Are we dead? No, I smell gas … which means we’re seconds from dead.

I pulled off my helmet. Mike ran up the hill and lifted the motorcycle; gas trickled onto my legs. He rolled the bike out of the way and I sat in the dirt. My boots were shiny from fuel, so I unbuckled the clamps and pulled them off.

“Dude!” Mike said. “Are you okay?”

I stretched my arms, twisted my back. Ouch. “I’m alright.”

He turned a boot upside down and gas drizzled out. “Geez! What happened?”

“No clue.” I eyed the hill, looking for the rock or stump that had flipped me. Nothing but tracks and gouged earth. “Guess I was going too fast.”

We need to get you home, Harvey said. Something might be broken.

Mike helped me stand and we inspected the motorcycle.

“Your handlebars look bent. Hmm, and your clutch lever. But I think it’s ridable. What about you?”

I dropped my pants to check the pain in my thigh and found a grapefruit-sized welt.

Harvey winced at the sight. Tomorrow, that’ll be a lovely purple badge of honor. Your award for being a dick.

A trickle of blood on my arm, a few scrapes, and dust on my face was the extent of the damage. “Ridable,” I said with a nod.

Harvey’s eyebrows rose. Ridable? I don’t think so. We need a doctor. You might have serious internal bleeding!

Mike handed me my helmet. “I hate to admit, but I saw you flying through the air and my first thought was ‘there goes Alaska.’ When the bike landed on you, I thought you’d broken your back.”

That night, I nursed my aches in a steaming tub and ignored Harvey ranting in the background. No cracked bones on my body or broken parts on my motorcycle: I’d dodged a bullet.

I’ll be more careful from now on.

He stopped ranting. You promise?

I sank into the water. I promise. A broken back or broken anything was the last thing I wanted. Especially in the Alaskan wilderness.

Our next planning session, two weeks later, involved more planning and less crashing. We compared notes, read blogs, and leafed through Milepost Magazine, an extensive Alaska road trip guidebook.

“Top of the World Highway is first on my list.” He tapped the road on our map.

“I have to see Denali National Park,” I said. “And Mount McKinley.” An image of a black and white TV from my preschool days filled my mind. Sunday afternoons I’d sit on the back of our couch, lean against the wall, and dangle my feet above the cushions. Wild Kingdom was on.

“Denali? Done.” Mike traced a line across the Denali Highway to Top of the World Highway.

His words sounded muffled because I’d time-traveled forty years back to where that little boy’s eyes were glued to the television. Grizzly bears caught salmon with their teeth. Glaciers crashed into the ocean, and wind blew snow off the tallest peak in North America. At five years old, I’d known my life would be spent exploring the amazing places Marlin Perkins showed me every week. I watched the little-tyke’s eyes dance with wonder. His awe inspired on one hand, but stung on the other. Because I knew the truth of the next forty years. I broke away from the blissful torture before tears made things awkward with Mike. Maybe something in Alaska could revive and heal that little guy.

“I want to come back … changed,” I said, almost to myself.

Mike stopped tapping. “Yeah.”

Change? The past few years had been some of my best: depression in check, relationships solid, international travels. But, something was missing. When had that boyish smile fizzled? Eleven? Twelve? An image flashed: Harvey. To protect me from bullies, Harvey had banished the child.

Maybe that’s why I needed this trip. To find a boy lost somewhere in that massive wilderness. I saw myself speeding away from an Alaskan farm with a ten-year-old Warren on back—while Harvey played clueless in a meadow.

Harvey looked up from his copy of The Milepost. What?

Nothing. I erased the farm and boy before he could see.

Ask Mike where he wants to leave his father’s ashes.

No way, Harv. I’m not asking him that.

Why? Don’t you care? You’ll need to add that place to the plan.

Mike was studying a picture of Dawson City, where Top of the World Highway ended. Was that where he’d take his father? Did thoughts of his father drum up pain? I wanted to ask, but couldn’t.

It’s personal, Harvey. If he wants to talk, he’ll bring it up.

Whatever.

By July, and with a month to go, our plan had increased to five lines:

1. Go To Alaska on Motorcycles

2. Denali National Park/Mt. McKinley

3. The Top of the World Highway

4. Leave on August 9th

5. Return better men

That’s a plan? Harvey said. That’s not even a proposal. That’s like NASA saying, let’s go to Mars. We’ll leave in 2025, take some potatoes, and we need rocket fuel. Is it too much to ask for a detailed itinerary?

Harvey, you complain with a plan, you complain without one. I make a list, you spout off ten reasons why it sucks … no matter how good or bad it is. I continued with a high pitched, whiny voice, That’ll cost too much, there’s not enough time, that doesn’t sound fun…

Fine, you made your point. And I don’t sound like that.

Stress should be a helpful friend—a nudge in the right direction. Not a monster living in my head.

He glowered; his lip quivered. You really think I’m a monster?

No, and stop pouting. Remember Torino?

Four years prior, Aubree and I had gotten lost in Torino, Italy—sweaty, hungry, and wandering like confused rats. We had left the train station, dragging luggage clickety-clack over cobblestone streets when we should have been relaxing in our hotel room. I held up the name of our hotel and locals smiled, gestured, and talked slowly—as if that could make us understand Italian. We followed pointing fingers that way, then this way—one road after the next, for hours.

This is why you stay home, Harvey had said. How often have I warned you about being lost in a foreign city where you don’t speak the language?

All the time, Harvey. All the damn time. It was one of my greatest fears when traveling.

Aubree’s eyes drooped with exhaustion, but she trekked, without complaint, up and down another road. I faked confidence and reassured her, but I’m sure she saw through the facade. I was lost and didn’t speak the—

I stopped. I’m lost in Torino, it’s dusk, and I can’t speak the language.

Duh, Harvey replied.

I’m experiencing one of my greatest fears! This is a greatest moment of my life!

I think the heat fried half your IQ points. This is not a win … not something to relish. This, Warren, is failure. Loathe this moment and keep walking.

Harvey had used that exact situation to keep me from traveling, and the reality fell way short of his horrific projections. Inconvenienced, hot, tired—yes. But hungry, homeless, and cold? No. We’d find our hotel and live to enjoy another day in Italy. I suddenly knew how Superman felt when he discovered he could leap tall buildings. I, too, had a secret power.

No, Harvey, you’re wrong about the relish. Watch this. I stepped into the street, lifted my hand, and summoned a taxi. Call me Taximan.

More like Maxipadman. You can’t spend money on a cab … it might cost fifty bucks for five blocks. They overcharge foreigners. Now, get back on the sidewalk.

We climbed in the back seat. Problem solved. A solution less about superpowers and more about yanking my head from my ass. Why had I let stubborn ideas make life unnecessarily difficult? Who made the rule that we always walked from bus stations to the hotels?

Get out and walk to the hotel. That is the plan. Harvey stomped his foot.

Oh, that’s right. Harvey’s rule.

I showed the name of the hotel to the driver, and, twenty minutes later, Aubree and I collapsed on soft beds in an air-conditioned room.

You know, Harvey, I’ve learned an important lesson about traveling today. Things aren’t as bad as you say they’ll be, I’d told him.

The Torino reference silenced Harvey’s complaints about an Alaska plan. The churning in my gut subsided. Alaska, like Torino, would be fine.

Later, while on the phone with Mike talking about the upcoming NFL season, he changed the subject. “What do you think about a ferry? I’ve read a trip to Alaska isn’t complete without a boat ride up the Inside Passage.”

My mind shifted from Beastmode dragging linebackers and Russell Wilson scrambling from tackles to a steamboat surrounded by icebergs. “Yeah, I can picture that.”

Wrong generation, Cabin Boy. Harvey punched his keyboard; a ferry docked in Bellingham appeared on his monitor.

“Three days on a ship to Haines would throw us right into Alaska,” Mike said. “And, we can camp on the top deck. Set up our tents and everything.”

“Tents? On a ship? But Mike, we’ll sink it when we hammer in our pegs.” The steamboat and icebergs returned to my mind—now with a tent pitched on the deck. It looked fun. “Okay. Camping sounds better than hiding out in a cabin, plus saves money, I’m guessing.”

“Yup. But the drawback is we’ll have to leave a week later because of the ferry schedule.”

I smacked the table. “Damn.”

Yes! Harvey raised two fisted hands. Finally, good news.

No kidding, I agreed with Harvey. Then I hit the table again to fake my frustration to Mike.

Hey Einstein, Mike’s on the phone. He can’t see you.

*

One month before turning over our souls to the Spirit of Adventure, we worked on bikes and built toolkits. One of our final tasks was mounting new tires. Gertrude wore tubeless tires—flat repairs wouldn’t require pulling off rubber. On the other hand, if Tiger got a flat, the wheel had to be removed, tube patched, and everything put back together. A bit of work, but no problem.

Seriously? Harvey said.

Heck, yes. I can change a bicycle tire … it can’t be much different.

Of course. He punched his head in mock stupidity. Because they both have two wheels. I’m such an idiot.

What do you know? I realize it’s not the same. Jason’s gonna show me, and I’ll mount the new ones myself. Not a big deal.

Yeah, we’ll see, he said.

At Jason’s, the demo took a half hour—because I kept asking questions and recording the answers with my cell phone. Otherwise, the process would have taken ten minutes.

“Easy as pie,” Jason said.

What’s up with motorcycles and pie? Harvey asked.

Pie’s awesome, motorcycles are awesome … duh! I said.

A new set of tires would last the whole trip, so we bought new, dual-sport tires—treads designed eighty percent for the street, twenty for off-road. Highway miles would be smooth and gravel would feel solid, but we’d have to avoid mud, sand, and snow. On a sunny Saturday morning, Mike and I cranked Iron Maiden—’cause we were tough men—and fired up the air compressor for a two-hour job. Four hours later, we stopped for lunch and left our motorcycles naked in a mess of tools and bolts littering the garage floor. The new tires were not installed because we couldn’t get our back tires off the rims.

After lunch, I said, “Let’s roll the floor jack out and use it to pinch the tire against the hitch of my truck. Maybe that will force it off.”

That worked.

Nice job. Harvey scribbled on a sticky note. I’ll add ‘floor jack’ and ‘back end of your truck’ to the packing list.

“Yes!” Mike said. “But we better add the floor jack and back end of your truck to the packing list.”

Harvey roared with laughter.

“We should probably each pack a floor jack. To be safe,” I said.

“Good thinking.” Mike didn’t crack a smile.

When he wasn’t watching, half my mouth curled and I shook my head. Our dry humor had one rule: the first to laugh, loses.

Late in the afternoon, we gave up on Tiger and focused on Gertrude so Mike could go home. A few hours and many cuss words later, he rode into the darkness and left me to finish. I slogged past midnight and had almost finished—wheels were back on the bike, but the front tire wouldn’t lock to the rim. The bead wouldn’t set. Like an orange peel removed and wrapped back on the fruit, the tire didn’t hold. I couldn’t ride on a peeled orange, so I grabbed the compressor hose.

I’m going to keep filling until it pops into place, I told Harvey.

The pressure gauge passed thirty-three pounds, the recommended pressure. Forty-five. Fifty.

Harvey’s eyes bulged. How much pressure can—?

Sixty. Seventy. Hard as a rock, but, still, not on the rim. I’m sick of this. This’s gotta work.

Eighty.

Harvey backed to the side of my head furthest from the air compressor. He crouched to the floor. Maybe you should—

Ninety.

Stop! Harvey yelled, hands over his head. It’ll pop, but not to the rim. It’ll take off your face!

I stopped. Harvey was right. This was stupid and dangerous. I pressed the release valve; air hissed like a feral cat, and I jumped as if sharp claws had swiped at me. The tire deflated, I turned off the compressor, the garage light, and slammed the house door behind me. I’d failed. Failed. Instead of crying, I went to bed cursing.

*

I woke early, went straight to the garage, and picked up where I’d left off—at failing. All day. Called Jason, my dad, scoured message boards, searched YouTube videos, but nothing helped. Someone online suggested dousing the rim with starter fluid and striking a match to pop everything into place. I watched a demonstration, and it appeared to work…

No. No, no, no, and absolutely, no. Harvey pointed to the shelf. Put the lighter fluid back and walk away.

Fine.

I dribbled the wheel down the sidewalk like John Stockton.

Not even close to John Stockton, Harvey said.

I heated the rubber with a hair dryer.

Now that’s cute. Gonna get out the curlers next?

Against my wife’s advice, I put my motorcycle back together and rode slowly down the street. Nope. Late Sunday night—with two precious days wasted on a two-hour job—I lay, exhausted, on the floor. My bike was un-ridable and a long list of weekend tasks remained untouched.

Why is this so difficult? What am I doing wrong?

Harvey rolled his eyes. Wrong? How about CHANGING YOUR OWN DAMN TIRE?

With my cheek against the cold, greasy cement, I caved. You win, Harvey. Tomorrow when Les Schwab is open, I’ll take it in.

Monday morning, I tossed the wheel in the back of the truck and stopped at Les Schwab on my way home from work. Later, they’d laugh in the back room at the idiot who’d screwed up his motorcycle, but I needed help and wanted to know what I’d done wrong. A tire dude rolled my wheel towards a wall of fancy gadgets. That was it. I didn’t have fancy gadgets.

He didn’t touch the gadgets. He slapped fluid on the rubber, pumped air, and started rolling it back to me. Sixty seconds. And done.

What the hell? Harvey’s mouth hung open.

What the hell indeed. What had I done wrong? If I couldn’t succeed with my air compressor, garage tools, and YouTube videos, how did I expect to repair flats in the grizzly-infested wilderness?

“There you go, no charge,” the tire dude said.

I gaped. “How’d you do that?”

“You need to use tire grease, not WD40,” he said. “That’s what you said you used? WD40?”

I nodded.

“Tire grease.” He smacked the tire and walked off.

I bought tire grease, went home, and tried it myself. Snapped right into place. Lesson learned.

Why weren’t there easier ways to find quick fixes for frustrating problems? I remembered a long drawn-out argument years before with my first wife. I’d told a buddy weeks would pass before my life returned to normal. He’d said there might be a way to resolve the situation. I doubted it, but he was a therapist, so I listened. My eyes popped wide. How had I missed that? I went home, made a suggestion regarding our personal time, and listened to her thoughts. Within ten minutes, the huge fight had been over.

Tire grease.

But if I didn’t know tire grease existed for a given scenario, what could I do? Where could I search? Sometimes, all I could do was keep plugging away. Like I had this past weekend. As long as I searched for tire grease and left the lighter fluid on the shelf, I could eventually figure anything out. Almost anything. I figured neither tire grease nor lighter fluid could have saved my first marriage.

*

Thursday night, Alaskan Adventure Eve, I inspected Tiger. Three pieces of hard luggage carried most of my gear: a top box above the rear tire and two side boxes (panniers). A large waterproof duffel bag (dry roll) rested on the seat behind me and another smaller bag on the gas tank (tank bag). Despite everything, I was ready.

I’ve never felt this confident before a trip.

Hmmm. Harvey scratched his chin. Maybe you should do one last review of the message boards. For good luck.

Not a bad idea. I booted the computer and scanned key websites.

Stop! Go back! Harvey slipped off his chair and jumped in for a closer look. He pointed. There! Your hard luggage has a twenty-pound limit. Sixty for the three pieces. Were you aware of that?

I wasn’t.

I took the bathroom scale to the garage and removed the topcase and panniers. The first weighed forty-two.

We can shuffle things, I said before Harvey lost it. I’ll find out which is the lightest and move stuff around.

The second weighed forty-four. Harvey paced, mumbling, and I put the third on the scale. I needed a reading of negative twenty. Instead, the lever stopped at forty-one.

Sixty-seven pounds over? Sixty-seven? Triple the recommended weight?

Double, not triple, I said.

Whatever. Harvey sat and started punching keys on his computer.

Before you do that… But I had nothing. I shut my mouth and waited for the horror I knew was coming.

He pressed ‘enter,’ and a video played—my motorcycle on the Alcan Highway. Side bags vibrated, teetered, and dangled by one bolt. A dip in the road, the bike rocked, panniers tumbled. Bounced. Shattered. Clothes, tools, camera equipment flew—tires squealed. A van rolled, burst into flames; mother, father, and children screamed in horror.

There is your future, he said.

Why hadn’t I purchased the expensive, durable cases? How had I missed this?

The trip is over, Harvey said. This isn’t a case of paying twenty-five bucks at the gate. This is dangerous … cancel-the-trip dangerous. You better call Mike.

For the next three hours I researched, rearranged, and argued with Harvey. I tried to lighten my load but failed. Leave my camera? Tools? Food? I needed everything. Which meant the rack holding my panniers could break. And how would the extra weight impact off-road performance and tire wear?

At 3:00 am, I went to bed without removing one ounce. My stomach ached like I’d taken a punch to the gut, and I tossed all night. The two mistakes had shoved me off a confident perch onto the ledge of uncertainty. I stood on a cliff with tire grease and heavy luggage—not a good idea. Where mistakes meant a thousand-foot death plunge. What else had I overlooked?

Torino mantra? Screw Torino. We could have been mugged and Aubree taken to Albania to be sold into slavery.

One hundred and eighty-eight pounds of equipment and supplies were loaded on my bike.

That’s like a passenger, I realized, feeling better. Tiger can handle it.

That’s not the problem … it’s your mounting racks, Harvey said.

You saw the message boards. Everyone overloads. Plus, I don’t think the limit includes the luggage … just the contents. Those were on the scale too, remember? That changes everything.

He shook his head. Nope. You never confirmed that.

I hadn’t, and wouldn’t. If I was wrong, I couldn’t handle the truth. The bike was loaded and tomorrow we had a ferry to catch.

I’m going to Alaska in the morning if it kills me.

It just might, Harvey answered.

Great story I will read your book soon